|

John H. Patterson

Prophet of Change

To the younger generation of Dayton John H. Patterson is largely a name, but to the older generation he lives in retrospect as a great industrial executive, a virile civic leader, and the community’s foremost citizen.

The ancestry and background of John H. Patterson helped to shape his  career and give him the heritage of courage and aggressiveness which were among his dominant qualities. He sprang from sturdy Revolutionary stock. In his blood flowed the pioneer strain that had wrested part of the western wilderness from savage men and beasts. Farm-bred, he was reared on hard work. Unremitting work became the watchword of his career. He had a profound respect for the dignity of toil, for he had known it from his earliest boyhood. career and give him the heritage of courage and aggressiveness which were among his dominant qualities. He sprang from sturdy Revolutionary stock. In his blood flowed the pioneer strain that had wrested part of the western wilderness from savage men and beasts. Farm-bred, he was reared on hard work. Unremitting work became the watchword of his career. He had a profound respect for the dignity of toil, for he had known it from his earliest boyhood.

Patterson’s early manhood was spent amid the first great era of industrial expansion, born of American invention and enterprise. Eli Whitney had pioneered the way with his cotton gin; Cyrus McCormicks reaper had launched a new agricultural era. The mastodon which was to be The Standard Oil Company had already become a giant in the production of petroleum and its products. With his air brake, George Westinghouse had given the railroads a greater degree of safety. Andrew Carnegie was laying the foundation of United States Steel while Edison and his associates were expanding the use of electricity which was to spark the advance of man and production. In Detroit Henry Ford would soon be tinkering with the horseless carriage which was to put the nation on rubber tires.

Such was the epoch that started the United States on its march to industrial supremacy. It was the new age of machines that stirred the ambition of the youth of the land in the same way that the potentialities of the newborn nuclear age evoke enthusiasm in the young of today. Events proved that Patterson was destined to join this industrial cavalcade and become the militant force behind the development of a miracle of mechanism - the cash register - which was to bestow its manifold benefits wherever men and women work and trade.

The present-day Daytonian who lives in a well-heated house with electric lights; who goes to and from his office in bus or car along well-paved streets; who has ample fire and police protection, will think that he has gone back to an almost primitive age if he visualizes himself in the Dayton that witnessed the birth of John H. Patterson in 1844. James Polk had just been elected President. The West, with its Golconda of mineral wealth and its vast fertile area awaiting the plow, was still to be won. Dayton’s population was between 6,000 and 7,000. There was no bank; no railroad; no telephone; no telegraph; no hospital. The center of retail business was Second and Jefferson. People used candles and lamps to light their houses. At night streets were lighted with torches, tar barrels, or bonfires. Citizens traveled by horse, buggy, stage, or cars which ran n wooden tracks. What became a Century of Progress had not yet struck its stride.

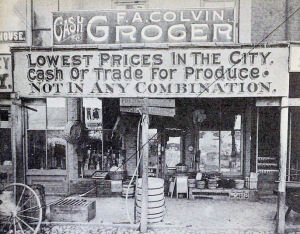

In those days merchandising everywhere was scarcely less primitive than the facilities for everyday life in Dayton. The storekeeper used his pocket or a cash drawer as repository for the money he took in. When John H. Patterson was thirty-five years old - he had successively been school teacher, canal tollkeeper, coal mine owner, and coal merchant - something happened that was fated to afford him the opportunity to capitalize his great gifts and to give Dayton a far-flung industrial prestige. primitive than the facilities for everyday life in Dayton. The storekeeper used his pocket or a cash drawer as repository for the money he took in. When John H. Patterson was thirty-five years old - he had successively been school teacher, canal tollkeeper, coal mine owner, and coal merchant - something happened that was fated to afford him the opportunity to capitalize his great gifts and to give Dayton a far-flung industrial prestige.

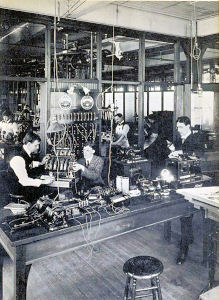

This is the thing that happened: On the second floor of a two-story building on the east side of Main Street a Dayton cafe-owner named James Ritty developed the first cash register. He got the idea on shipboard at sea as he watched an indicator register the revolutions of the ship’s propeller. He had been losing money in his business. What he wanted was a machine which would give publicity to sales and thus remove temptation. The propeller indicator provided the clue. The first cash register was the result. That crude mechanism, born in the dawn of what has become a magic era of mechanization, was as logical in principle and as unerring in purpose as the telephone and the automobile.

While operating his coal mines John H. Patterson ran a general store at Coalton, Ohio. Although he did a big business he found he was losing money. The moment he heard of the cash register he ordered two for the Coalton store. With their introduction his profits increased because the leakage stopped.

The purchase of those cash registers marked the decisive turning point in Patterson’s life. He saw far more in the cash register than a mere recorder of sales. He envisaged it as a necessity to retail business - a keeper of the business conscience. Realizing its vast potentialities for development, he and his brother, Frank j. Patterson, bought the National Manufacturing Company which made the first registers. In 1884 it became The National Cash Register Company which will always be synonymous with John H. Patterson’s career.

NCR became his life and passion, charged with something of the fire and fervor of a crusade. Under his compelling, driving power and his effective technique of salesmanship, both geared to intensive product improvement, he reared a world-wide organization. Like that famous Revolutionary shot fired at Lexington, the bell of the cash register today is heard around the globe.

What, then, were the qualities in John H. Patterson that made him an outstanding industrialist and humanitarian? For one thing he had the simplicity which always attaches to greatness. His energy and enterprise were almost without limit; his vision boundless.

This story is typical of the man:

When he was in the coal business he sold Jackson County coal. It was good coal but sometimes it had to be coaxed before it caught fire. Perhaps it was temperamental. It followed that on occasion Patterson had complaints about his coal. He heeded these complaints in characteristic fashion. Although co-head of the coal business, he visited homes, went into kitchens, and showed cooks and housewives how to get a fire started. There were no caste lines in his teaching code. He went from fashionable houses on First Street over to humble homes across the river. Being what in these days is called a socialite, he would often leave an exclusive dance early in the morning, get a few hours’ sleep, and turn up in somebody’s kitchen almost before the household was astir.

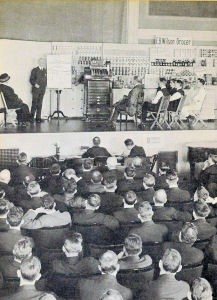

At the root of the Patterson business creed was the value of education which meant training. He applied it to every detail of his production and selling. Always the pioneer, he established the first sales school in the United States; he believed that salesmen are not born but made. He created a technique of selling, embodied in a literature of salesmanship, that has become a classic in its field.

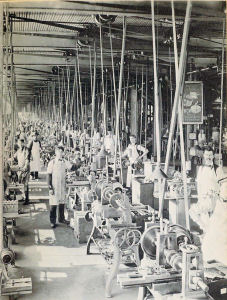

Patterson was a realist in life and work, nowhere more effectively than  in meeting emergencies. Early in his industrial career a shipment of cash registers was returned to the factory from England because of defective workmanship. It was a blow to prestige and profit. Patterson acted in his usual way. He moved his desk into the factory where he found out what was wrong. The factory was dark and dirty; the water for drinking and washing unclean. Discontent ruled at lathe and bench. Overnight he remedied the situation. The factory was cleaned. Each worker had his individual locker. The men were satisfied. No more defective cash registers came back. in meeting emergencies. Early in his industrial career a shipment of cash registers was returned to the factory from England because of defective workmanship. It was a blow to prestige and profit. Patterson acted in his usual way. He moved his desk into the factory where he found out what was wrong. The factory was dark and dirty; the water for drinking and washing unclean. Discontent ruled at lathe and bench. Overnight he remedied the situation. The factory was cleaned. Each worker had his individual locker. The men were satisfied. No more defective cash registers came back.

Something larger and deeper than content and efficiency in work was wrought by this change. Patterson learned then that close contact with his factory force was the basis of real industrial relations. That first dingy work room was succeeded before many years passed by the first American daylight factory with 80 per cent of the walls glass. His formula for working conditions and labor relations henceforth embodied the three elements of Head, Hand, and Heart. They were the expression of practical altruism and spelled business success. What he did in those faraway eighties was the basis upon which much of modern industrial management is reared.

One day not long after the factory episode that has just been described, Patterson saw a woman factory worker warming a pot of coffee on a radiator. It gave him the inspiration to provide hot meals for women employees.

This was the beginning of employee benefits in American industry. The hot meals were followed by rest periods, dining rooms, medical service with a dental clinic, visiting nurses, health education, recreational grounds, motion pictures during lunch, clubs for employees, night classes, and vacation and educational trips. The era of employee benefits began.

Such measures at the factory pointed the way to civic improvements for Dayton. It began with the beautification of the factory neighborhood which meant the redemption of “Slidertown” from a slum area. Idle boys broke factory windows so Patterson started garden clubs for them. The clubs ended mischief, eliminated juvenile delinquency, and started the boys on the road to useful citizenship.

The boys’ clubs were the nucleus of Patterson’s larger service to Dayton . Improvement of the city, like the NCR business, became a crusade evolving about the community idea. With his inherent love of beauty he started school gardens which were a step toward adornment of the city. He fostered the first kindergarten, the community center, neighborhood clubs, playgrounds and a country club, Saturday morning entertainment for children, and cooking centers in schools. He topped all this with the gift of 300 acres of his Hills and Dales estate to the city. . Improvement of the city, like the NCR business, became a crusade evolving about the community idea. With his inherent love of beauty he started school gardens which were a step toward adornment of the city. He fostered the first kindergarten, the community center, neighborhood clubs, playgrounds and a country club, Saturday morning entertainment for children, and cooking centers in schools. He topped all this with the gift of 300 acres of his Hills and Dales estate to the city.

Beauty, recreation and education comprised only part of his ambitious scheme for Dayton. His instinct for organization gave him the strong conviction that a city should be run as efficiently as a business. This meant clean government and confusion to the professional politician. Largely due to his efforts the city manager plan, long his dream, became a reality. Animating all his many-sided civic efforts was the desire to make Dayton a healthier and happier place to live in.

One event stands out preeminently in any estimate of John H. Patterson. It was the great Dayton flood of March 1913 when the waters of the Miami, the Still- water, and the Mad Rivers went on the rampage inundating the city and bringing loss, grief, and misery to a large part of the population. In that dark hour the Patterson genius for mercy and organization asserted itself to invoke the undying gratitude of a whole community.

As the angry, rain-swollen waters began to rise Mr. Patterson viewed the growing desolation from the roof of the NCR office building. He said: “Dayton will have a tremendous flood today. We must prepare to house and feed the people who will be driven from their homes. I now declare NCR temporarily out of commission and proclaim the Citizens Relief Committee.”

By every available wagon, truck, and motor car he rushed bedding, medicine and hospital supplies to the plant. He ordered a special train-load of supplies from New York. He built boats, mobilized doctors, nurses, and relief workers. Thousands were rescued from their flooded houses and brought to the factory which expanded into a huge relief camp. NCR hill became Sanctuary Hill. medicine and hospital supplies to the plant. He ordered a special train-load of supplies from New York. He built boats, mobilized doctors, nurses, and relief workers. Thousands were rescued from their flooded houses and brought to the factory which expanded into a huge relief camp. NCR hill became Sanctuary Hill.

Those grim flood days that marked the high tide of Dayton’s turbulent waters marked also the high tide of Patterson’s humanitarianism. The waters receded but there was no recession in his public service.

Patterson’s leadership did not end with the end of the flood. Dayton lay prostrate in a sea of slime. Thousands of people, discouraged and disheartened over the ruin about them, wanted to leave the city. Again Patterson rose to the emergency. As head of the Citizens Relief Committee he urged the people to remain and redeem the community. He rekindled the fires of their faith. Dayton emerged reborn from the ordeal to fulfill her destiny.

John H. Patterson was often misunderstood, criticized and opposed. Like many outstanding men of big vision, he was ahead of his time. His constant maxim was “We progress through change.” Life and work for him meant constant change but change that produced improvement whether with men or methods. He formulated principles and practices that have stood the test of seventy-five years. Thus he became a great teacher; a trainer of men. Graduates of NCR head important business enterprises throughout the United States. Like many outstanding men of big vision, he was ahead of his time. His constant maxim was “We progress through change.” Life and work for him meant constant change but change that produced improvement whether with men or methods. He formulated principles and practices that have stood the test of seventy-five years. Thus he became a great teacher; a trainer of men. Graduates of NCR head important business enterprises throughout the United States.

Patterson’s will to do was indomitable, his spirit unconquerable. Kipling could well have had him in mind when he wrote: “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster and treat those two imposters just the same…” Like the same Kipling character, he could “walk with Kings nor lose the common touch.” The “common touch” for him meant kinship, understanding and uplift of his fellow man. He was part and parcel of every phase of his company’s advancement. NCR today is the “lengthened shadow” of John H. Patterson;

Patterson was almost undersized, with gray eyes, florid complexion, sandy hair and bristling moustache. He was a little man with a dynamo inside, who was both doer and dreamer. There is no better index to his character than is to be found in his favorite Bible text which was: “Do justly, love mercy, walk humbly.”

Emerson once said: “The history of the world is but the biography of great men.” So, too, with the saga of American industry. In its Valhalla, so rich in its record of outstanding achievement, John H. Patterson ranks among the elect.

The Year NCR Was Founded

In the year 1884 Dayton hardly qualified as “the city beautiful.” From one end of town to the other there was not a single paved street. In wet weather ankle-deep mud stimulated the bluest profanity of teamsters and spattered pedestrians. In dry weather great clouds of dust made housewives think wistfully of life on the farm.

Most of the city was even more dismal at night. A few electric street lights had been installed downtown a year earlier, but flickering gas lamps lit the dingy side streets. A small army of boys, equipped with lanterns and torches, served as the local lamplighters.

A handful of the wealthier citizenry had telephones in 1884, but a sewage system was several years away. About the only major municipal service was a waterworks. In all of Dayton, there was not a single public playground.

The mud, debris and general lack of sanitation kept the city’s several doctors busy at the bedsides of the ailing among the 40,000 residents. “Epidemic” was much more than a word to describe what happened in some faraway place. The life expectancy of the average man was about 45 years. His wife could look forward to an additional two years.

Yet the Dayton of 1884 was in the midst of one of the city’s most progressive decades. It had grown so fast that the Courthouse made ‘indestructible” by Lincoln’s brief stop had already become hopelessly inadequate. The “new” courthouse, built to ease the pinch, had just been completed. St. Elizabeth’s hospital on 1-lopeland Street was only two years old, but already its 200 beds were filled to capacity. The City Council had unloosened the municipal pursestrings sufficiently to acquire Daytons first paddy wagon, at the same time allotting $1,100 to buy horses for mounted police to deal with ruffians on the outskirts of the city. progressive decades. It had grown so fast that the Courthouse made ‘indestructible” by Lincoln’s brief stop had already become hopelessly inadequate. The “new” courthouse, built to ease the pinch, had just been completed. St. Elizabeth’s hospital on 1-lopeland Street was only two years old, but already its 200 beds were filled to capacity. The City Council had unloosened the municipal pursestrings sufficiently to acquire Daytons first paddy wagon, at the same time allotting $1,100 to buy horses for mounted police to deal with ruffians on the outskirts of the city.

The Phillips House, with 140 rooms, and the Beckel House, with 150 rooms, represented two of the Midwest’s finest hostelries. And although the Third Street bridge was still a covered, wooden structure, the Main Street bridge was now a steel span which had successfully withstood the severe flood of 1883.

Business in Dayton was booming. The Barney & Smith Car Company, largest industry in the city, was trying hard to keep up with the demand for its railroad passenger and freight cars. It was even manufacturing sleeping cars for George Pullman before their inventor discovered that making the cars himself was far more profitable.

The Buckeye Iron & Brass Works had already been in business for 40 years; Lowe Brothers for 12; Reynolds & Reynolds for 18; Dayton Malleable Iron for 18; F. A. Requarth for 20, and Joyce-Cridland for 10 years.

Nationally, the parade of events in 1884 - both major and minor - included the first baseball game played under electric lights, in Fort Wayne, Indiana; the invention of the first practical cigar-rolling machine, by Oscar Hammerstein, uncle of the librettist; the laying of the cornerstone of the Statue of Liberty; the publishing of Frank R. Stockton’s famed short story, ‘The Lady or the Tiger?”; the first glider flight in America, by John Joseph Montgomery, and Grover Clevelands victory for the presidency over James G. Blame by a vote of 4,911,017 to 4,848,334.

Life was conducted at a relatively easy pace. Almost two decades had healed most of the scars of the Civil War and the age of industrialization was coming into its own with the promise of prosperity and plenty for all. had healed most of the scars of the Civil War and the age of industrialization was coming into its own with the promise of prosperity and plenty for all.

The leisurely eighties were not always so leisurely in Dayton, however. In July of 1884 occurred one of the most strenuous civic celebrations in Dayton history — the dedication of the Soldiers Monument. For two days, celebrities, citizens, and fortyish veterans of the Grand Army of the Republic shot fireworks, made speeches, held parades and pageants, and otherwise cavorted. On hand to lend prestige were ex-President Rutherford B. Hayes and Union General W. S. Rosecrans. At the critical moment of the unveiling of the statue, however, the veil refused to budge. Ex-President Hayes pulled on the rope in vain; then General Rosecrans tugged mightily as the crowd tittered. Finally, the dilemma was solved. A steeplejack ignominiously tossed a lasso around the head of the statue, climbed the rope and ripped away the veil amid the cheers of the assembled multitude.

A little later two “gunboats” moved sluggishly down the Miami River as thousands of Daytonians lined the shores to witness a mock naval engagement between the “Mississippi River ironclads,” one Union and one Rebel. The boats, hastily made of boards, were propelled by paddles which in turn were powered by handcranks. Amazingly, they held together long enough for several salvos to be fired from the field pieces and mortars on the decks. Then, as the crowd again roared, the crews jumped into the water, waded ashore, and staged another mock Civil War battle, this time on land.

Entertainment of another type had also come to Dayton that year. Before a capacity crowd at the Grand Opera House, Mark Twain kept his audience laughing for two hours with readings, joke-telling and impromptu asides. A newspaper critic reported that the best part of the evening was Twain’s selection from his unpublished book, ‘Huckleberry Finn.’

And in December of 1884, the month he founded The National Cash Register Company, John H. Patterson was reported in the same newspaper to have been among those who took part in informal sled races. The races, a tradition in winter months, were held on First Street on Sunday afternoons. Patterson drove a horse called Sorrel Dan, but the paper reported that “it wasn’t Sorrel Dan’s Day.” Performing much better that wintry afternoon, according to the paper, was a horse named Jim McConnell. And the driver of Jim McConnel was James Ritty, inventor of the cash register, who three years before had given up hope that his machine would ever amount to anything financially. For $1,000 Ritty had sold his patents to the firm that in 1884 became NCR,

Source: NCR 75th Anniversary Booklet

|