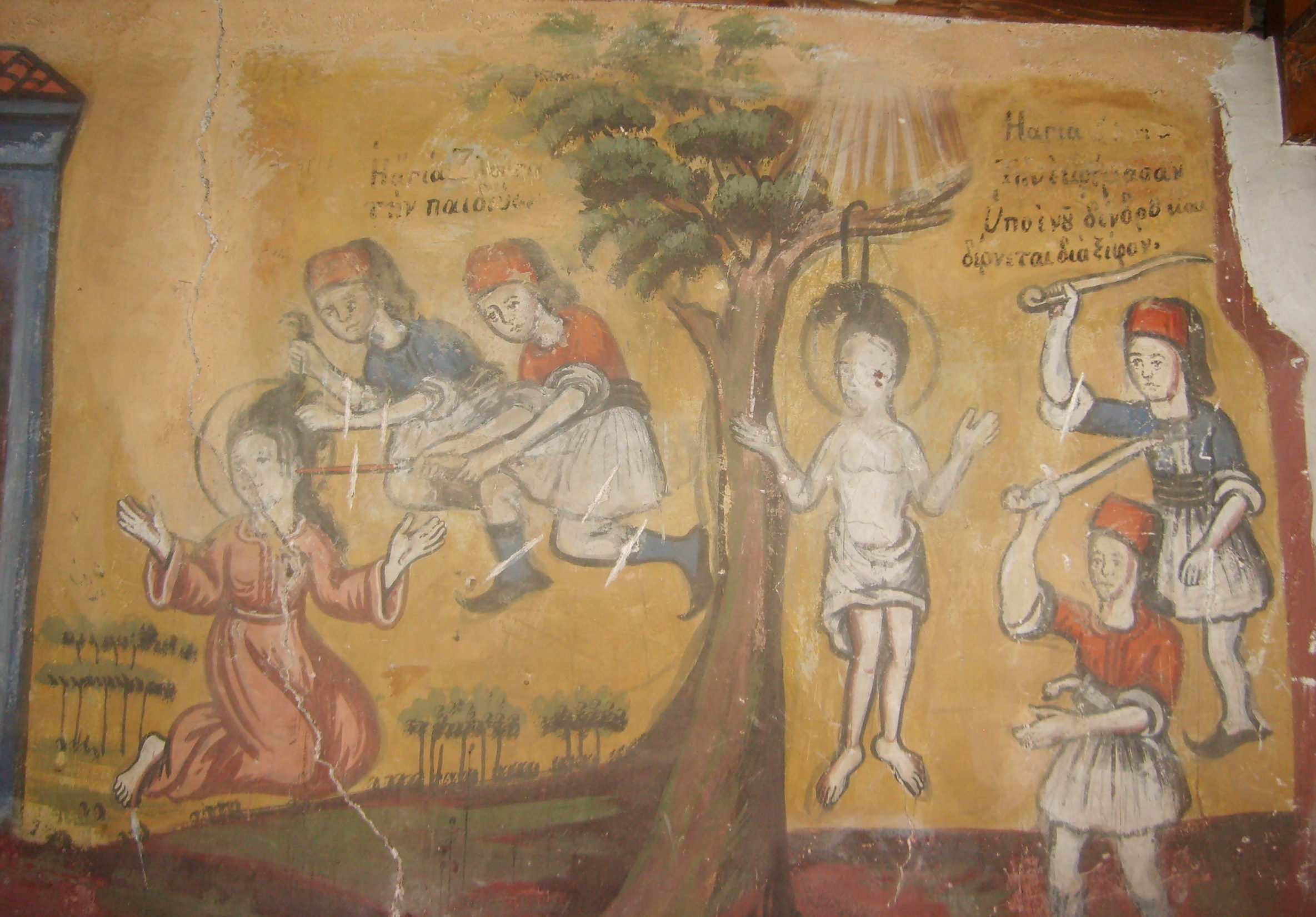

“Dendrites hanging on a tree of life blooming in virtues, like a good fruits of the Spirit”

The monasticism is born in the late antiquity in the desert to Egypt, Syria, Palestine and Asia Minor, in a peculiar dialogue with the development of urban Christianity.

As we know, Christianity is a city religion, the structure of it is following example of administrative organization common for the age in the Roman Empire.

With the end of the anti-Christian persecution, church the christian communities in the city of the empire to strengthen, grow, and move on to onether new way of development – with all pluses and minuses for a new state. Freedom to confess (worship) gradually retreating locally to patronage of the empire, which with its whole repressive power stands on the side of the new religion, who has conquered for its four centuries of existence with it’s evangelic radicalism, won the hearts of many thousands of Roman citizens. This puts the Christian communities in front of the unknown for them challenge, being a Christian now provides additional citizen advantages for better arrangement of lifely affairs. The wine of the apostoles preach to unreservedly following of Christ is now inter-mixe with the common for a man conformity.

This comes to be a problem for many Christians and most importantly for those who do not want (or cannot) live with their Christian identity in conditions of the Imperial Church.

Hence, the end of the persecutions coincides with the stormy flourishing of monasticism and ascetism, in all regions of the empire from the end of the east to the external borders of the western parts. In the church life is born a single center, which is trying to remind the believers that the Kingdom of God is not from this world, but instead every christian is called to secretly raise his own seed of faith in his field (the good and clean heart) – in secret and independently from the worldly rulers.

Among the diversified forms of cenobitic monasticism and asceticism, present during the early Byzantine period, a typical one known for its radicalism of faith and asceticism of Syrian Christians. It is in the midst Syria where the phenomenon of monastic stylites “pillars” e (στυλίτες) they have a specific hermit type of life, in whose the monk lives on the top of open or closed “tower” or high stone, without coming to earth, in constant prayer, regardless of climatic conditions. Stylitism has received a wide spread between the Orthodox and Monophysitites to theEast, but not among the Nestorians (early christian heretics). Among the well known Stylites are Saint Simeon Stalpnik (Stylites) (lived in 5th century), Daniil the Stylites (5th century), Simeon The-Newest (Novi) and Alipiy the Stylites (6th century).

Having formalized the whole course in monasticism, so-called open monasticism. monasticism is openly (του ανοικτού μέσου), to whose branch a part are the Stylites and the Dendrites δενδρίτες (the monks who lives on a tree or inside a tree), monks who live without a shelter. „βοσκοί”. Other extreme forms of ascetism are the “recluse” (οι έγκλειστοι, κλωβίτες), they are part of the the so-called. "closed type" monasticism (του κλειστού μέσου), the most notable saints representatives from this type are the elders Barsanuphious and elder Ioan (Elder).

Among the most unusual and rarely practiced forms of asceticism was dendriticism. These ascetics remain in the Romance languages with their Greek name – dendrites – inhabiting trees. They lived inside, in the hollow, or in the branches of the tree, standing or sitting. Their feat is compared to that of the columnists, who also live in a small space on tree posts or pillars. The small space they occupied for varying periods of time—usually from one to several years—developed in them the virtue of manly patience. Dendrites "serve God in the trees", these wonderful creations of God, among whom a chosen one become the Holy Christ cross tree that served for the salvation and sanctification of man. With their "blessed solitude" they become the new "witnesses of conscience" after the end of the "witnesses of blood" who deserved and won eternal life in the persecutions of the Roman Empire.

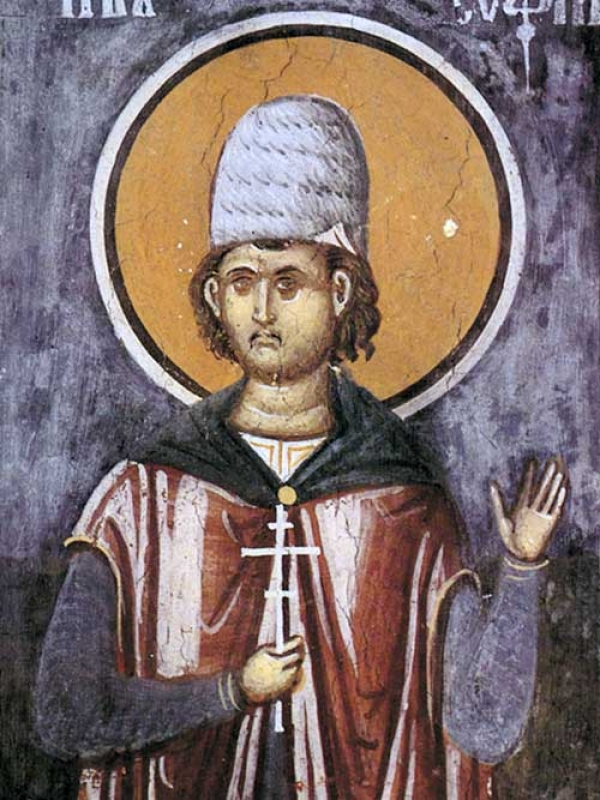

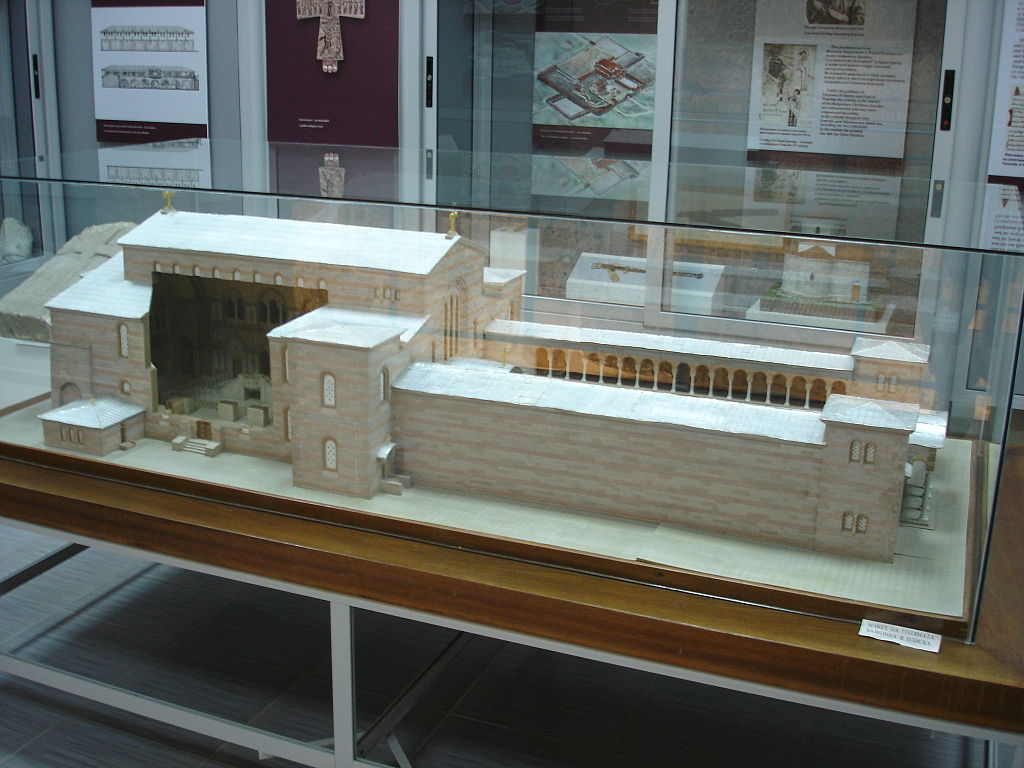

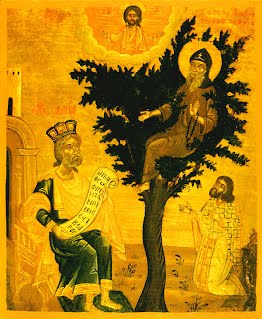

St. David of Thessalonica But as we said, the creation of a common monastic culture in the spacious borders of the Christian Empire brought this exotic way of life to the West as well. Pillars appear even next to the walls of the capital city – in the person of St. Daniel the Pillar, and Rev. David of Thessalonica (6th century) is among the most famous hermits-dendrites not only in the Balkans, but also in the entire Christian world. And although he spent three years on the almond tree in prayer and fasting, after which he continued his feat on a pillar, in Orthodox iconography he remains immortalized precisely on a tree. And the second hermit who went through this ascetic test was St. John of Rila, the founder of monasticism in the Bulgarian lands.

![]()

But as mentioned, the creation of a common monastic culture within the spacious borders of the Christian Empire brought this exotic way of life to the West.

Pillars saints appear even next to the walls of the capital city – in the person of St. Daniel the Pillar, and Rev. David of Thessalonica (6th century) is among the most famous hermits-dendrites not only in the Balkans, but also in the entire Christian world. And although he spent three years on the almond tree in prayer and fasting, after which he continued his feat on a pillar, in Orthodox iconography he remains immortalized depicted precisely on a tree. And the second hermit who went through this ascetic test was St. John of Rila, the founder of monasticism in the Bulgarian lands.

The way of thinking of people in ancient times was very different from the modern way.

All ascetic Byzantine literature testifies to the desire to see in every detail of everyday life a lesson, a symbol, a sign of divine providence in the life of every person.

In this sense, the feat of the ascetics-dendrites is rich in Christian symbols and metaphors. The hymnography of the Church in their glorification highlights two main elements – of the tree of life, to which they become partakers with their feat, and of the freedom of complete surrender in God's hands, inherent in the "birds of the sky", who do not care for their sustenance, but rely on God's mercy.

This is what the first symbol looks like – on the tree not as an ordinary residence, but as an image of the Cross of Christ.

"The dendrites hanging on the tree of life flourish in virtues as good fruits of the Spirit", and in the service of St. David of Thessalonica – the most famous monk in the Balkans who experienced this way of asceticism, we also read:

"Like a light bird he climbed on the tree and made a hut, freezing in winter and burning in summer. Thus he obtained the golden wings of dispassion and perfection, which lifted them to the heavens."

The tree is undoubtedly one of the most common symbols in Christian literature, dating back to the early church. Tertullian compared Christians to evergreen trees.

Origen compares Christ to the tree of life. For Didymus the Blind (4th century), the tree is the vine Christ, whose branches are the righteous men who bear true fruit. This imagery enters the language of church writers through the Gospel texts. The tree is a symbol that Christ himself used many times in his parables – I am the Vine of life… The fig tree that does not bear fruit withers and becomes useless. According to church teaching, "everything that died through the tree of the knowledge of good and evil will live again through the tree of the Cross and the water of baptism that springs from the Tree of the Cross of Christ." Pseudo-Ambrosius.

Clement of Alexandria says that the tree of the living Christ grows in the paradise of the Church, in the waters of renewal and gives as its fruit the teaching and the evangelical way of life.

All these symbols and metaphors of the tree as a symbol of the fall, death and salvation of man pass through the Gospel and patristic texts in the life of the ascetics and more specifically of those of them who choose the solitude of the tree as a place of their witness and feat.

During the period before the Christianization of the Bulgarian people, the Orthodox Church accumulated serious ascetic experience, represented in the monastic movement in its various forms. Different ascetics preferred different forms of asceticism, and each of them developed new virtues and spiritual gifts in the ascetics.

This priceless centuries-old experience grafted into the young Bulgarian Church and its first hermit, St. John of Rila.

The Church of Christ in Bulgaria found in him an ascetic who, within the framework of his life, managed to go through all the forms of asceticism that Christian monasticism had known up to that point – he created a new monastery, where he studied, then became a hermit, lived in a cave, in the open rock, in the hollow of a tree, and finally receives the charisma of spiritual fatherhood and gathers disciple monastic brotherhood.

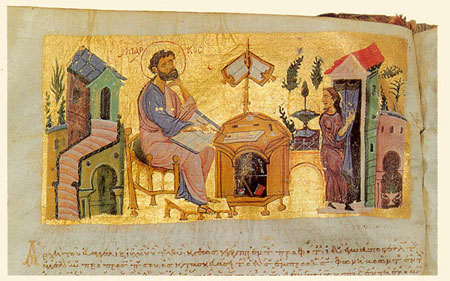

Already at the very beginning of the Long Life of St. John of Rila, we see the comparison of St. John with the popular Christian symbol of the fruit-bearing tree: "and it bore fruit, indeed a hundredfold, as a tree planted by springs of water."

As in the lives of the other dendrite monks, St. John did not immediately proceed to this difficult feat – he began his monastic journey "in a monastery for the sake of learning" and only then withdrew to the wilderness of the mountain, where he lived in a hut of branches.

Saint John then spent 12 years in a narrow and dark cave! (the cave is nowadays located about 50 minutes walk from the Rila monastery in the mountain of Rila)

The biographer of Saint John St. Euthymius informs us that only after that he moved "at a considerable distance" from the cave and settled in the hollow of a huge oak, like the oak of Abraham. It is obvious the desire of Patriarch Euthymius to make a connection between this unusual feat for this region of the Christian world and the hospitality of Abraham, who met the Holy Trinity under the Oak.

In the hollow of the tree St. John ate chickpeas. This is, by the way, the first mention of growing chickpeas on the Bulgarian lands – the chickpea is an unpretentious, but still heat-loving plant, which is grown mainly in the southern Bulgarian lands and Dobrudja today.

In the life, the sprouting of chickpeas around the oak of St. John of Rila is compared to the miracle of manna from heaven. The behavior of the shepherds who secretly collect pods of chickpeas from the saint and their unusual joy shows (they loot it) that this food was indeed atypical of the region where St. John traveled and it successfully growing on this mountain coldly place is one of the innumerable miracles of the saints which started even in his lifetime.

After that, exactly what is the logic of the ascetics-dendrites in the other popular stories about them – the sick begin to flock around the saint, his living invariably mention "possessed by demons" who come to heal to him.

The life of prayerful patience and extreme asceticism of these strange hermits living in trees reminded them of Christ's words that "this kind does not come out except by prayer and fasting."

Life conveys to us the prayer of the saint, with which he frees the possessed – from the text we see that it does not have an exorcistic character as in most of the other saint livings, that is, St. John does not directly forbid the demons, but calls on God's omnipotence and thus reveals his deep, extreme humility, with which he receives daring before God.

It is noteworthy to mention that Reverend David of Thessalonica also received the charisma to cast out demons after spending three years in the branches of an almond tree.

![]()

The duration of life on the tree for different ascetics is different – for Saint David it is three years, in the life of Saint John of Rila the time is not specified (most likely because the saint asked God to hide this part of his life again for humility).

Three is a symbolic number, corresponding to the request of the prophet David to receive from God goodness, knowledge and prudence. According to Susan Ashbrook Harvey, tree life "seems to have had the character of a temporary discipline in the ascetic practice, in which different places and modes of asceticism were changed." Unlike dendrites, those who live on a pillar spend many more years there, this way of asceticism also becomes a social service.

While life in a tree is usually a transition to some other asceticism, which means that as living conditions it was much more difficult. This is how Reverend David's life is described by his biographer: Further on, the author describes the sufferings of David in the (ἔν) tree – he was tormented by cold, by heat, by winds, but his angel-like face did not change, but looked like blooming rose. Some of his disciples went to the tree and begged him to come down and help them—lest the spiritual wolf prey on the flock while the shepherd was gone. David, however, was steadfast in his decision to remain on the tree. "I will not come down from the tree for three years, then our Lord Jesus Christ will show me that he has accepted my prayer."

Three years later, an angel appeared to him and told him that God had heard his prayer and ordered him to come down from the tree and build himself a cell, because another mission (οἰκονομία) awaited him.

It is interesting that at this point David turns to the official church authority for a kind of sanction of the vision ‒ he sends his disciples to tell what happened to the bishop of Thessalonica, Dorotheus and ask him whether this vision is really from God.

Researchers of monastic culture in the Byzantine era note the greater remoteness, isolation of the ascetics-dendrites from those who live on pillars. Entire temporary settlements of pilgrims, sick people, people from different tribes and countries arise around the latter, which often make noise and disturb the ascetic life of the saint. The most famous example is Rev. Simeon The Stylite ( Stulpnik ) the founder of hermit Stylitism. Around his pillar there was always a crowd that was not always meek, obedient and pious. There are often half-wild Arabs among her, sometimes 200, 300, 1000 people to come.

They often made a noise and continued their tribal quarrels at the foot of the pillar.

However, the dendrites immediately leave the place of their feat if people begin to gather around them – be they pilgrims or disciples. We see this in the life of Revend John as well:

"And the valiant Ivan, as soon as he learned what was happening, got up and went away from there, because he was afraid, and even more, he hated human glory."

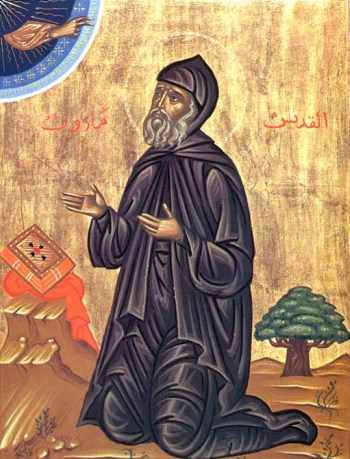

We see this clearly expressed in the lives of two brothers in Syria – Rev. Maro (Saint Maron passed on to Christ 410 AD) and Rev. Abraham.

The first was a dendrite, and the second a stylite.

John of Ephesus in the Lives of the Eastern Saints tells of the Reverend Maro(n) Dendrite that he lived in a hollow tree near his brother Abraham, a stylite in his monastery.

Unlike the monks, St. Maro did not communicate with visitors, the door of his tree was closed, and he lived in silence until someone sought healing.

When his brother died, Maro left his imprisonment in the tree and moved to his brother's place and then began to communicate more with people.

But while living in the tree, Maro received no visitors.

Like Reverend Maron in Syria, Saint John of Rila leaves the tree of his asceticism as soon as people begin to gather around him, and switches to another form of asceticism – very close to stair climbing, namely on a high and difficult-to-access rock (today known as the Rock of Saint John a common place for pilgrimage).

But even here, tempted and physically injured by the demons, the ascetic does not remain hidden from the people. It was during this period that he attracted the attention of St. King Peter, who tried to establish contact with him. Of course, the high rock on which St. John of Rila lived for seven and a half years provided much harsher living conditions than the steeple, which is usually near a populated place. But as a philosophy of the ascetic feat, in both cases it is about something in common – maximally narrowing the free space for movement and directing all energy upwards, in the power of prayer and constant unity with God.

The common moments in the lives of the two most famous Dendrite monks in the Balkans – Revend David of Thessaloniki and St. John of Rila, who labored three centuries are similar.

Both begin their monastic journey with "discipleship in a monastery" before heading for the desert, that is, moving away from human society.

For both of them, the life in the oak, respectively in the almond branches is a period of extreme asceticism, which greatly impresses the surrounding population, who begin to flock to them. Their unusual feat inspires in people a desire to live near them and even to imitate them – in their lives we see a number of people who seek their help – starting with students (one of Reverend David's students also became a "dendrite" as his mentor and settled in the hollow of a large tree). There glory quickly reaches the local bishop and all the clergy, as well as the rulers of the city – as mentioned in the life of the Thessalonian ascetic, and to Saint King (Tsar) Peter and the Bulgarian boyars as mentioned in the biographical life of Saint John of Rila .

The biographers of both monks include the stories of the healing of demoniacs precisely while they were living in their unprotected "homes" from the natural elements – i.e. the trees. Finally, for all their desire to remain hidden in the wilderness of their solitude, they attract not only the sick, the afflicted, and the disciples, but the attention of the powerful of the day.

But while St. David came from the East, from Mesopotamia, St. John was local and did not have a great Eastern ascetic teacher as he was local citizen born in Bulgaria, in our lands.

His way of asceticism is undoubtedly influenced by the general ascetic patterns of the age, but it is also unique – it is a testimony to the general internal logic of Christian asceticism, regardless of which parts of the Christian world it is practiced.

Paradoxically, the brightest monastic examples in the Balkans became precisely these two monks, struggling in these harsh, atypical for the western parts of the empire, conditions – dendriticism, stylitism, living in a narrow cave and a high cliff.

Until the 9th century, that is, throughout the early Byzantine period, in today's Greek lands, the cult, the respect for Rev. David of Thessalonica (born c. 450 – 540) was comparable only to that of Saint Great-Martyr (Demetrius) Dimitar of Thessalonica and St. Achilles, bishop of Larissa.

Great Respect and recognition as a saint for him was already alive in the first half of the 9th century at the same time when saint John’s greatnes shined upon the world, as we can see from the life of St. Gregory the Decapolitan, who sent one of his monks to worship at the saint's grave in a monastery founded by him near Thessaloniki. St. David the Dendrite monastery was an attractive pilgrimage center in the Balkan lands of the empire until the 11th century, when the relics of the saint were brought by the Crusaders to Italy.

Without the spiritual presence of its founder, its monastery declined and disappeared, and its relics returned to Thessaloniki only in the 20th century and were laid in the church of "St. Theodora".

The abode of the Rila desert dweller has a different destiny – it remains as a living spiritual center throughout the centuries, in the heart of the Rila desert, and its founder, already a resident of the Heavenly Jerusalem, invariably remains a faithful and reliable breviary for his kindred in the flesh the Bulgarians.

Report presented at the international conference dedicated to the 500th anniversary of the transfer of the relics of St. John of Rila from Tarnovo to the monastery he founded, organized in 2019 at the Rila Monastery. It was published in the eponymous collection of conference reports under the title: "Dendrite Monks in the Balkans".

Article originally posted in Bulgarian by Zlatina Ivanova on 19.10.2022 – Translated with minor modifications by me (Georgi D. Georgiev a.k.a. hip0)